Typically, I steer away from bluntness when writing these blogs. I don’t like to say, “Hey, you. Yes, you. I think you need this book in your life.” But, I think it is appropriate to say that here about Birds in the Sky Fish In the Sea, a collaboration by Matthew Dickerson and Matthew Clark.

So, if you would spare me some room for bluntness: Hey, you. Yes, you. I think you need this book in your life and it is because I am convinced after reading this that our eyes are poorly trained when it comes to attending to creation. Maybe that doesn’t sound like a case so bad that it requires immediate intervention to you, but I would bet all my chips that you’ll think otherwise when you realize the power and glory of that which your eyes have missed out on.

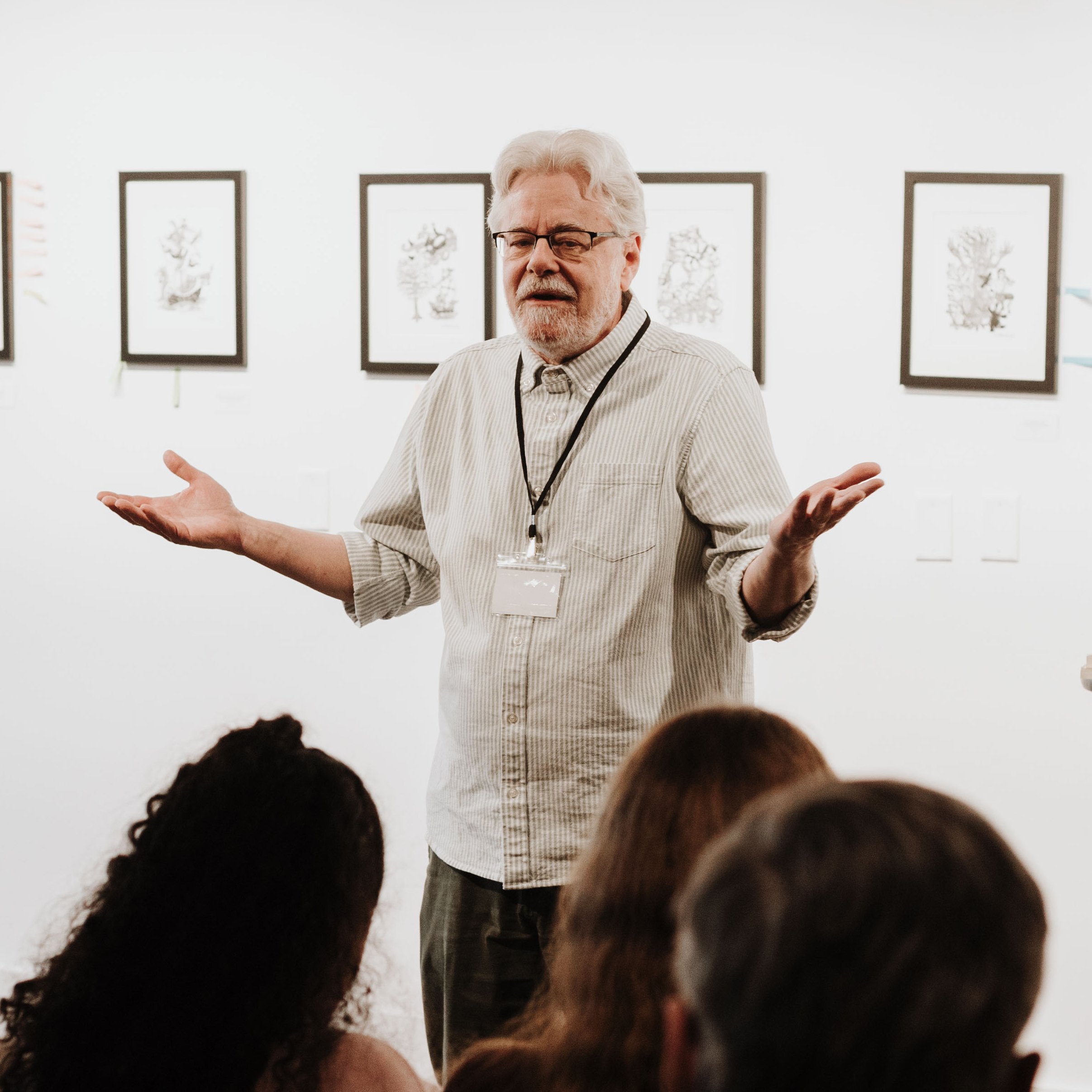

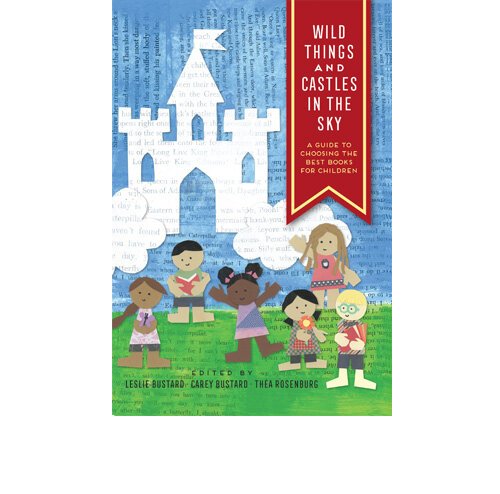

Matthew Dickerson has been clued in on it for years, though. He is a professor at Middlebury College, author of Aslan’s Breath, last year's keynote speaker at the Square Halo 24 conference, has served on the board of directors of the Outdoor Writers Association of America, and has been selected as artist-in-residence for Glacier National Park, Acadia National Park, and Alaska State Parks. The core of this book is attentiveness to creation, creation being the deliberate loving act of Creator who brought beauty into being. Dickerson writes and Clark illustrates, but there’s a bit more to it than that. This book is concerned with changing the way you interact or offer your attendance to creation, but in doing so, I also felt it asked me to interact and attend differently to the book itself. Clark’s illustrations (long-time fans of Square Halo will recognize Clark’s work from Revealed, Ordinary Saints, and other of our titles) are framed by Dickerson’s short theological essays and then narrative nonfiction and poetry. It is not a book to be rushed through. Each illustration, poem, and story within it was like a meditation in the wild that deserved a loving act of beholding.

I said you will realize that which you have missed out on. Dickerson writes on observing bears, the woods behind his home, salmon, thimbleberries, herons, walks with his dog, and rivers. He offers a theology of why bears go through the extra effort of searching for female salmon and their eggs rather than feasting on the males, but also a theology for scenes as common as crayfish in a lake and how one might see the gospel in that. I am certainly guilty of passing by creation too busy, too distracted, or honestly too bored by the scenes I perceive to have little for me to benefit or take from. I am amazed by the capacity of both Matthews to pay not just attention to creation, but pay loving attention to it. That is where I feel I have often gone wrong.

My attention to creation is not always loving attention. Alan Jacobs in his book, A Theology of Reading, The Hermaneutics of Love, says,

“The kind of pleasure we take in a well-crafted work of literary art is very like the pleasure we take in a well-cooked meal, in that it is something given to us by another person. It is a gift that we honor, and whose giver we honor, by receiving it with gratitude. It is not always appropriate, it is not always charitable, to take that which is offered to us in a spirit of pleasure and recreation and use it according to a rigid criterion of studious application.”

I am often consuming the world around me with a spirit of furious application, indifferent to the fact that it is a gift charitably given for me to be received. The creative works of both Matthews in this book are testaments to how the eyes of a man can see things differently and much more brilliantly when his hands learn to open up those clenched fists which were only good for squeezing the life out of that which he could grasp for his study and consumption to instead receive the world as a gift with open hands.

This is solace for me now.

You have conjured that for me,

like this place. You plucked

the celestial strings. The rest

will wait until the morning

of the resurrection.

Heaven was conjured for you. It is essential to learn how to see it.

This post was written by Ian Mozaffarian